Memories of a Neighborhood Boy: Melvin Nesbitt Jr.

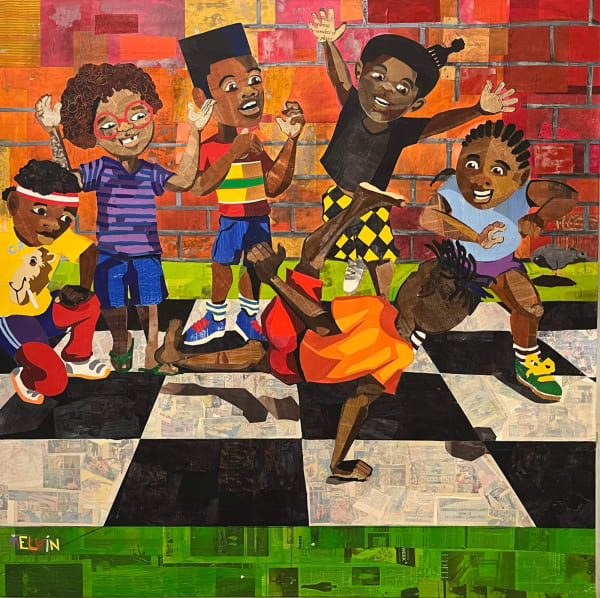

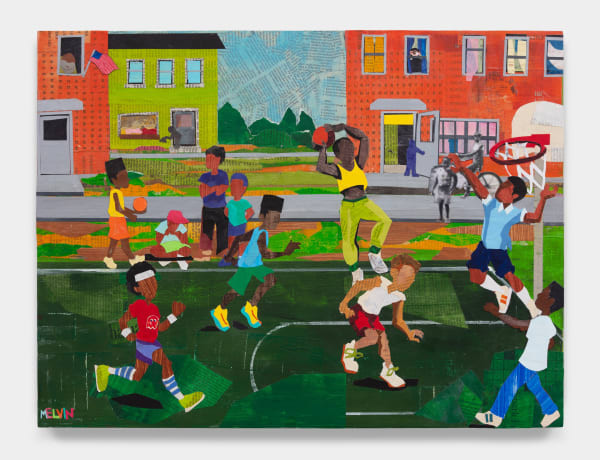

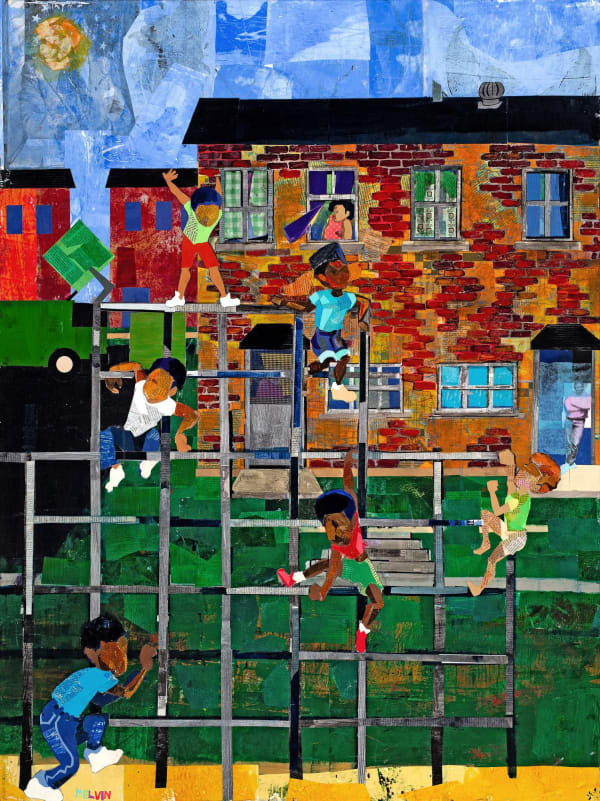

Collagist Melvin L. Nesbitt Jr. (b. 1973) repurposes paper to create the pages of a book he would have loved as a child. The Washington, D.C.-based artist explores themes of boyhood, community, and play in his solo exhibition Memories of a Neighborhood Boy, on view at Richard Beavers Gallery from April 22, 2023 to June 3, 2023. Above all else, the multidisciplinary artist has set out to create scenes of people who look like him via recycled, repurposed materials. Self-taught until his early 30s, Nesbitt enrolled in painting and drawing classes at the University of the District of Columbia; he felt uncomfortable about the cost of materials, and it wasn’t until he pivoted to collage—a medium that requires minimal material waste—that he felt truly free to experiment. Today the artist uses whatever paper he can access: discarded newspaper from the D.C. metro, or perhaps a recycled puzzle book; postage stamps, comic books, and dictionary pages are also treated in his works. Nesbitt will manipulate paper to make it more archival—to give it an aged look—before adding layers of acrylic medium, and subsequently paint. He may include washes, or swaths of crayon or pastel, to repurpose the papers more effectively.

This manipulation is essential to the artist’s storytelling approach. It also pays homage to the way Nesbitt lived: recycling materials as much as possible before discarding them, and relying on hand-me-downs as a young boy. “I’m searching for an aesthetic that works as coded language to the viewer who shares my experience,” the artist explains. Nesbitt lived in public housing from kindergarten through sixth grade, before relocating to rural Spartanburg, South Carolina, and Memories of a Neighborhood Boy shows Black children who grew up like him that there can be real joy in their communities. During his youth, the artiat felt great shame about his origins—reluctant to disclose he lived in poverty, and disappointed that he so rarely saw subjects who looked like him in art and media. Yet his memories were happy.

To reflect this, Memories of a Neighborhood Boy moves away from trauma, including recent discussions surrounding race and racism, and shows the human side of Black communities. The collagist captures a specific moment in time: a snapshot of young people engaged in the present, not yet aware that being poor or Black could make navigating society more challenging. Rather than examining trauma in the literal sense, the artist puts the lens back on pleasure. He envisions children from public housing communities visiting a gallery or a museum, and seeing something familiar in the artwork—witnessing their lives reflected back to them. “I want to let them know their stories are an important part of the American fabric,” he elaborates.

Nesbitt listens to music while he works: R&B from the late 70s and 80s, hip-hop and rap, lots of Michael Jackson. The artist’s studio soundtrack is reminiscent of his childhood; Nesbitt’s father and brother were musicians, while a bevy of paternal relatives were singers. Describing Memories of a Neighborhood Boy, the artist acknowledges that some of his friends didn’t even know their fathers growing up—so they learned from one another how to be. This, the artist explains, is the major difference in the current body of work. The focus on boyhood and community is palpable. In the works, paper is a metaphor for Black Americans, and the artist brings this comparison to life with vast, immersive scenes. “In a lot of places, we pick up more from other boys than we do from the leaders in our home,” he states. The artist views the discarded materials he uses as metaphorical in this sense. Waste, recyclables, and litter are viewed as having little value, despite coming from one of humanity's most valuable natural resources—trees—and despite societies printing their currencies on this material. In this same vein, Black people have been the source of a great deal of innovation and wealth building—yet outsides discard—devalue, even—the values and traditions of the Black community. “People meet me for the first time and assume I'm a low-life or predator until something shows them I actually have value,” Nesbitt elaborates. “This goes with my decision to use paper as a medium and to teach collage—I want to challenge the idea that High Art requires the use of expensive materials, which makes becoming an artist even less accessible for people without money.” The artist hopes to challenge elitist ideas about value by recognizing the value of objects that we tend to overlook. He leverages the coming-together of disparate pieces of paper to create something new—something of value—from pieces that were once considered trash. This parallels members of a community uniting for a common cause.

Speaking of community, Nesbitt’s collages depict his childhood persona—nicknamed Junebug—and his friends Peanut, Slick, and Deuce. Dare Me (2023) features two boys on a swing, one of them so high it’s as though he wants his friend to dare him to jump. The work underscores the playful competition in which young boys engage, with hints of identity and manhood in the subjects’ body language. It speaks to structures of power, and to how some of our peers hold remarkable influence over us.

Mother’s Day Off (2023) honors the artist’s mother, who looked forward to the occasional day off from work so that she could catch up on tasks around the house. For her, there was no day off—yet she loved her home and children. The work showcases a woman at work in a bustling neighborhood: a community where sons help their mothers with the laundry, where single mothers work part-time jobs, and where female figures take on leadership positions in their communities—remaining steadfast in their comparative youth and lasting beauty. That’s My Song (2023), in this same vein, shows the artist as a young boy, dancing in the living room with his brother, sister, and their mom. Nesbitt sheds light on those fun times, celebrating family and community throughout. The overarching goal is to capture the preciousness of Black youth—to recapture that fleeting innocence—on recycled, repurposed paper. Viewers won’t want to look away.